Classification of global solutions to the obstacle problem

OpenYear of origin: 1992

Posted online: 2020-02-18 17:23:53Z by Henrik Shahgholian

Cite as: P-200218.1

This is a previous version of the post. You can go to the current version.

Problem's Description

Isaac Newton in his Principia (first book Ch. 12, Theorem XXXI) asserts that spherical shells exert no gravitational force in the cavity of the shell. This result was later extended to (ellipsoidal) homoeoid by P.-S. Laplace, using computation, and soon after by J. Ivory, using a more geometric approach; a homoeoid is the domain bounded by two homothetic ellipsoids with a common center.

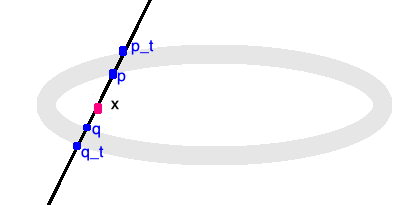

Ivory's proof is based on the following simple observation (for ellipsoids). Let $E = \{x: \ \sum_j a_j x_j^2 < 1 \}$ ($a_j > 0$) be an ellipsoids in ${\mathbb R}^n$ ($n\geq 2)$ (Ellipse in dimension 2), centred at the origin. Set $$ E_t := tE, \qquad t > 1 \qquad (\hbox{dilation}).$$ Let $x \in E$, and $L$ be any line through $x$. Then

i) $L$ cuts $\partial E$, at 2 points: $p, q \in \partial E$, on each side of $x$,

ii) $L$ cuts $\partial E_t$, at 2 points: $p_t, q_t \in \partial E_t$, on each side of $x$.

Ivory's Lemma:

$$|p-p_t| = |q - q_t|.$$

Using spherical coordinates with center $x$ we have $$ E_t \setminus E = \{y: \ y = x + r\omega , \ \rho (\omega) < r < \rho_t (\omega) \} , $$ where $\rho, \rho_t$ are respectively the equation of the ellipsoids $E, E_t$ in spherical coordinates with pole at $x$.

Define the Newtonian potential of $M \subset {\mathbb R}^n$, with density $c_n$, by $$ V_M (x) := c_n\int_{M} \frac{ dy}{|y-x|^{n-2}} . $$ In dimension 2 one needs to take logarithmic kernel. Here we have assumed $M$ is such that the integral exists, and we have chosen $c_n$ as a normalization factor such that $$ \Delta V_M := \nabla \cdot \nabla V_M= -\chi_M. $$ $ \nabla V_M$ is the gravitational field of $M$. Here $\Delta $ is the Laplace operator, and $\chi_M $ the characteristic function of $M$. For $x \in E $ we have

$$ \frac{1}{(n-2)c_n}\nabla V_{E_t \setminus E} (x) : = \int_{E_t \setminus E} \frac{(y-x) dy}{|y-x|^n} = \int_{{\mathbb{S}}^{n-1}} \int_{\rho(\omega)}^{ \rho_t (\omega)} \frac{ r\omega r^{n-1} dr d\omega}{ r^n} $$

$$ = \int_{{\mathbb{S}}^{n-1}} \omega R(\omega) d\omega , $$ where $$R(\omega ) = \left[ \rho_t (\omega) - \rho (\omega) \right] , \qquad y - x = r\omega,$$ and $d\omega$ is the differential solid angle; in ${\mathbb R}^3$, $d\omega = \sin \theta d \theta$, $0\leq \theta \leq \pi$. By Ivory's Lemma $R(\omega) = R(-\omega)$, and therefore $$\int_{{\mathbb{S}}^{n-1}} \omega R(\omega) d\omega = 0.$$ Hence the gravitational field $\nabla V_{E_t \setminus E} (x)$ is zero in the cavity, i.e. $$ 0= \nabla V_{E_t \setminus E} (x) , $$ for $x \in E$. Hence no-gravity in the cavity.

Rewriting the above we have $$ 0= \nabla V_{E_t \setminus E} (x) = \nabla V_E (x) - \nabla V_{E_t} (x) $$ and hence $$ \nabla V_E (x) = \nabla V_{E_t} (x) = t \nabla V_E (x/t) , \qquad \forall \ x \in E. $$ Therefore $\nabla V_E$ is degree one homogeneous in $E$. By continuity, each component must be linear. Hence $V_E$ is a quadratic polynomial $Q_E$ inside $E$.

By rigid motion of $E$, we can rewrite $Q_E$ as $$ Q_E= K_E - P_2 , \qquad \hbox{where } \quad P_2 = \sum_i b_{i} x_i^2$$ $$K_E >0 \ \hbox{ is a constant, } \qquad b_i > 0, \qquad 2 \sum_i b_i = 1.$$ We have used $ K_E = V_E(0) > 0$, and that gravitational force decreases as we move inside from the boundary, hence $$ \partial_{ii} V_{E} = \partial_{ii} Q_{E} = 2b_{i} > 0.$$

A result by Dive ( [4] 1931), and Di-Benedetto-Friedman ([5] 1986) states that

Ellipsoids are the only bounded domains with Newtonian potentials being quadratic polynomials inside the domain.

Proof (sketch): Let $D$ be the domain whose Newtonian potential $V_D$ is a quadratic polynomial $$V_D= K_D - P_2 , \qquad \hbox{inside }D .$$

There exists a smallest ellipsoid $E \supset D$ such hat $V_E$ is the polynomial $$V_E= K_E - P_2 \qquad \hbox{inside } E . $$ Dive did this by "simple" algebra using ellipsoidal coordinates. Di-Benedetto-Friedman used an iterative tracking method.

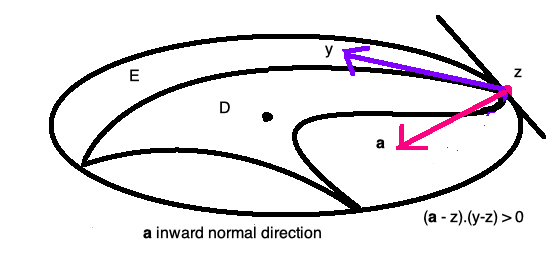

Obviously $K_E > K_D$, since $E \supset D$. For $z \in \partial E \cap \partial D$, a touching point of the boundaries, we have $$ V_{E\setminus D} = ( K_E - P_2 ) - (K_D - P_2 ) = K_E - K_D = \ Constant \quad \hbox{inside } D , $$ and in particular $$ \nabla V_{E\setminus D} = 0 \qquad \hbox{inside } D. $$

Compute the gravitation force at $z$ in the direction ${\bf a } -z$, and recall that $$ \nabla V_{E\setminus D} = 0 \qquad \hbox{inside } D. $$ Hence $$ 0= ({\bf a } -z) \cdot \nabla V_{E\setminus D} (z) = (n-2)c_n\int_{E\setminus D} \frac{ ({\bf a} -z) \cdot (y - z)}{|y-z|^n} dx > 0, $$ a contradiction. Therefore $D=E$, and $D$ is an ellipsoid.

Unbounded domains:

Can we define the concept for unbounded domains, e.g. limits of ellipsoids (paraboloids, half-planes, cylindrical domains)?

PDE formulation: Since for any ellipsoid $E$ we have $V_E = Q_E$ in $E$, we define $$ u(x):= V_E (x) - Q_E (x) \qquad x\in {\mathbb R}^n, $$ and obtain a global solution to the obstacle problem. $$ \Delta u = \chi_{ E^c}, \qquad u=0 \quad \hbox{in } E , $$ $$|u (x) | \approx C|x|^2, \qquad \hbox{for $ |x| $ being large} .$$

This definition generalizes the above concept to limits of a sequences of ellipsoids:

A solution to the so-called obstacle problem $$ \Delta u = \chi_{ \Omega }, \qquad u=0 \quad \hbox{in } \Omega^c , $$ $$|u (x) | \approx C|x|^2, \qquad \hbox{for $ |x| $ \ large} .$$ is called a global solution. The set $\Omega^c= \{ u = 0\}$ is called the coincidence set.

It is well known [3] that $u\geq 0$, so that $\Omega = \{u > 0\}$.

Conjecture: Sh. 1992: The only global solutions to the obstacle problem are those whose coincidence sets are limit domains of any sequences of ellipsoids.

Theorem: (Eberle, Sh., Weiss, [6] preprint 2020)

Let $u $ be a global solution to the obstacle problem in ${\mathbb R}^{n}$ $(n \geq 6)$ $$ \Delta u = \chi_{\{ u > 0\}}, \qquad u \geq 0. $$ Suppose $D:= \{ u = 0\}$ is non-cylindrical in any direction. Then $ \{ u = 0\}$ is one of the following:

\textbf{ i) An ellipsoid.

ii) A paraboloid. }

If $ \{ u = 0\}$ is cylindrical in $k$-directions, then we can reduce the problem to ${\mathbb R}^{n-k}$, where the same conclusion holds if $n-k \geq 6$.

This problem can be solved in dimension $n=4, 5$ by adapting the technique from [6] (preprint 2020).

Open problems: The case of n= 3 remains unchallenged. For $n=2$ there is a complex function theory approach by Sakai [2], and later by Shapiro [7]. It would be interesting to see real analysis technique for this case as well.

No solutions added yet